Narratives and Drama in 1885

Author: Alan Long

The 1885 North-West resistance was a source of many eye-witness accounts that have been told and re-told in newspapers and history books for more than 100 years. The amount of secondary history written about this monumental event in North American history is understandably significant; enough to give many historians pause when they think of adding their own interpretations to the literature. However, many people in Saskatchewan still feel very connected to this history and continue to engage the historical process as they try to rethink the thoughts of the people involved in those significant events. Several scholars, new and experienced, continue to search the archives, reading and rereading the primary source material, in search of new angles on old stories that will expose a fresh understanding of certain individuals or groups not previously thought of. In the last five years at the University of Saskatchewan at least three MA theses have been written on aspects of 1885, with more sure to come.1 My MA thesis titled George Mann was not a Cowboy: Rationalizing Western versus Aboriginal Perspectives of Life and Death "Dramatic" History completed in October, 2007, began as an interest in the Aboriginal oral history of 1885, an area that has received relatively little attention in the academic community until recently. This work still consumes my interest as I continue to develop relationships with the Aboriginal community, and find additional evidence in various archives.

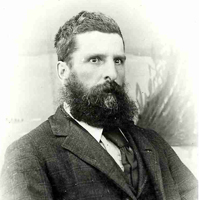

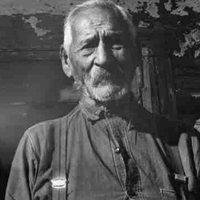

If you read the introduction to my thesis, you will see that my connection to the narratives of 1885 was my great great grandfather George Gwynne Mann's involvement in those events as a government farm instructor in Onion Lake, North-West Territories.

He came west from Bowmanville, Ontario alone in 1878, and was joined by his wife Sarah and their three children, Blanche, Charolette and George Junior in 1883.2

On the morning of 2 April 1885, Plains Cree Warriors in Frog Lake North-West Territories (approximately 25 miles north west of Onion Lake) decided to take matters into their own hands and killed nine white men in a tragic event that has become infamously known as the Frog Lake "massacre."3 Two of the men killed were farm instructor John Delaney and Indian agent Thomas Quinn, government colleagues of Mann.

Mann notes in his account of 2 April 1885 that when Quinn did not arrive "…I could see they (the Cree) were very excited. They expected to see the Ind. Agent Quinn from Frog Lake, who did not arrive as he was killed that morning with the others." (more: Transcribed text of George Mann's Account) Later that night Mann says he was warned by a "friendly Indian," about the men killed in Frog Lake, and so he decided leave everything and go to Fort Pitt. These were the only details he gave of that night.

In file A-751 of the Saskatchewan Archives Board Saskatoon office is a narrative written by Blanche Askey (nee Mann), who was Mann's oldest daughter and about 10 years old the night of their escape to Fort Pitt.

Blanche wrote down her story several times, the above version was probably the one sent to her niece's grade eight class in Battleford, Saskatchewan in 1923. Student Edna Beaudry added her own dramatic touches to Blanches original narrative in her essay.

Blanche also wrote her recollection down in 1935 when 50 year commemoration celebrations occurred in several Saskatchewan communities, and newspapers sought to publish stories from the ‘old timers' who were witness to events in 1885.4 The Prince Albert Herald published several first hand accounts of 1885 in their 1935 publications, and later compiled them into one volume titled "Reminiscences of the Riel Rebellion of 1885 as told by old timers of Prince Albert and District, who witnessed those stirring days." One of these stories highly dramatizes and sensationalizes the Frog Lake "Massacre."

As I discuss in greater detail in Chapter two of my thesis, drama played a role in the many narratives of 1885, especially in the mid-twentieth century as the development of a nationalist historical myth was well under way. Some of George Mann's descendants collected these stories and commented on the inaccuracies they found in them.

However, Blanche Askey was not immune to this influence, and I argue that aspects of her account show her own flare for the dramatic. In my thesis I connect this to a long held British tradition of defining dark skinned ‘others' in historical theatre and literature. The British would often paint their faces dark and become the ‘other,' sharing knowledge with each other about how they perceived these people to think and act. Since the completion of my thesis I have found pictorial evidence that the use of ‘blackface' or darkening up found its way into early twentieth century amateur theatre productions about Indians in Saskatchewan.

Aboriginal people and Aboriginal versions of similar events tended to be pushed aside in the face of these multiple dramatic narratives of the ‘Wild West,' which dominated the newspaper stories, historical literature and school classrooms of western Canada well into the twentieth century.5 If you read Blanche's account as you toured this exhibit, you may have noticed that she does not mention the names of the Aboriginal people that helped save her and her family that evening, referring to them only as "friendly Indians." Although this is not an inaccuracy it is quite a glaring omission, considering she and her family lived in Onion Lake for 17 years, and that they spoke Cree fluently. She shows this and other tendencies to follow the literary conventions of her fellow Canadians. Thankfully in 1985, when the 100th anniversary of 1885 arrived, there was a desire to revisit the narratives of that time, and to include Aboriginal oral history of the events. Finally, many of the names of Aboriginal people not previously highlighted began to be discussed.

Fortunately for my family a remarkable man by the name of Edgar Mapletoft, who lived and farmed near Onion Lake in the Fort Pitt District, led the Fort Pitt Historical Society when they assembled a local history of the Fort Pitt area called Fort Pitt History Unfolding.6 Although many local histories rarely engage Aboriginal oral history, a section of this work is dedicated to Aboriginal versions of the events of Frog Lake, Frenchman Butte and Onion Lake in 1885, material that Mapletoft was responsible for collecting. The original recorded stories of the elders in the Cree language have been digitized and preserved at the University of Saskatchewan Archives (Edgar Mapletoft fonds, Box 6, folder one and two).

Mapletoft had these stories translated and transcribed for their history book, including those of Jimmy Chief, the great grandson of Treaty Chief Seekascootch.7

According to Chief it was his ancestor Seekascootch and his son Misahew that were responsible for saving the lives of the Mann Family.

In chapter four of my thesis I put the transcribed oral history of Jimmy Chief alongside the narrative of Blanche Askey for comparison. Analyzing where these narratives diverged and intersected made for an interesting discussion, and sparked my interest in making further efforts to understand the Aboriginal perspective. In my work these narratives were the starting point of discussions between myself and members of both families, as I sought to understand how our families remembered this past today. This discussion is also a part of chapter four, as is the remarkable discovery I made when I interviewed elder Mary Whitstone. Her story was the first oral history I heard from an elder in Onion Lake, and set the tone for the rest of my work.

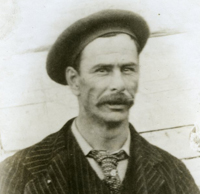

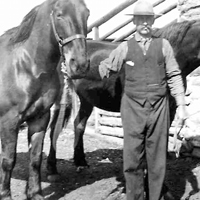

When I went to meet Mary, I wondered what new story she might tell that I had not obtained from Edgar Mapletoft's research, and discussions I previously had with descendants of Seekascootch. I was shocked to find out that she wished to talk about George Mann Jr., the son of Indian agent Mann and my great grandfather.

She told me that she had seen him when she was a young girl in Onion Lake, speaking Cree fluently to her parents. She said she was surprised to see a white man speaking Cree so well. While she watched him speak to her parents, Charlie and Matilda Trottier (nee Black), her older sister Mabel nudged her and told her that this white man was her father.

When I first heard this story I was shocked and embarrassed that I had never heard of this familial connection between my ancestors and the Cree people of Onion Lake. Mary's story reminded me how most of the Mann's descendants have become very much separate from the people there. This division was accentuated by the reserve system and Canadian historical conventions that have ignored Aboriginal versions of the past. Mary's story also helped me look at old family photographs in an entirely new way, and see things that were pushed aside in my mind by years of segregation. I found several images of George Mann Jr. with the people of Onion Lake, pictures that I looked at in a different light after hearing Mary's stories.

Mary also related to me that Mann Jr. continued to visit the people there long after his dad's transfer in 1900, to see his daughter and to visit the people he had grown up with.

In 1904, Mann Jr. married Barr Colonist Ethel Mary Burgess, and together they had four children.

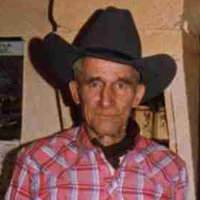

Their only son, George Reginald Tudor (Pete) Mann, was my grandfather.

Pete would often tell us stories of the past, like how an Aboriginal mid-wife delivered him and two of his sisters while the family lived in the north at the Moose Creek telegraph office from 1904 to 1910.

In 1910 they moved to a homestead near Lloydminster, where Pete spent the rest of his life. Pete would often tell stories about how active his family was, and how they loved to pack their wagon and head north on camping trips to visit friends.

When I combine these memories with the pictorial evidence and Mary's stories, it seems very likely that many of these trips were to see old friends in the Aboriginal community, people Mann Jr. had grown up in Onion Lake. Although it is not always evident in the historical literature, many new settlers of Canada had good relations with Aboriginal people. In my research I found that the Mann family began meaningful relationships with Aboriginal people after the trouble in 1885, and continued those associations into the early twentieth century.

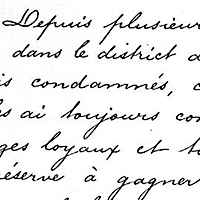

For example, in Métis Joseph Dion's book, My Tribe the Crees, he tells how Indian agent Mann had a good relationship with the people of Onion Lake. One set of archival records document that Mann sent a petition to Ottawa in November, 1887 to lobby for the release of three Aboriginal men that were convicted of murder in 1885, men that had helped ensure the safety of his family.

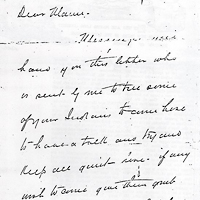

Mann Petition to lobby for the release of three men that were convicted of murder in 1885 (image details) |

In chapter five of my thesis I argue that this and other historical evidence suggests that Indian agent Mann's family helped create a strong community in Onion Lake, based on trust and mutual respect. These stories have become pushed away from our family and lost in favour dramatically influenced historical myths about cowboys and Indians, and not about human beings surviving and working together.

I recently hosted a get together of the descendants of George Mann Jr. and Matilda Trottier (nee Black) at my parents' farm near Lloydminster. At this gathering I shared some of my research and asked Mary Whitstone to speak to all of us about our extended family. I think that was the first time anyone has spoken Cree on our farm. Mary's stories have helped re-kindle relationships left stagnant by years of segregation and dramatic historical myth-making. When the Cree oral tradition was put side by side the Mann family's stories it inspired a fresh look at the historical evidence and began what I hope is a more balanced dialogue between cultures about a shared history.8 Kakiypaysinakatamakowiya, Our Legacy.

Notes

1. Paget Code, "Les Autres Métis: The English Métis of the Prince Albert Settlement, 1862-1886," (Thesis MA, University of Saskatchewan, 2008), and Erin Jodi Millions, "Ties Undone: A Gendered and Racial Analysis of the Impact of the 1885 Northwest Rebellion in the Saskatchewan District." (Thesis MA, University of Saskatchewan, 2004). back

2. The history of George Mann and his family's move west was researched by family member Frank Nash and is on file at SAB. back

3. The word massacre is put in quotation marks to denote that it is a non-Aboriginal term that presents this historical event in a one-dimensional way. As I allude to in my thesis, there is much historical evidence that casts considerable doubt on the assumption that it was an unprovoked and senseless act. back

4. These versions of her story can be found in the George Gwynne Mann fonds at the Glenbow Archives, Calgary, Alberta. back

5. Jerome Alvin Hammersmith, "The Indian in Saskatchewan Elementary School Social Studies Textbooks: A Content Analysis," (Thesis M. Ed., University of Saskatchewan, 1971). Please refer to the abstract of this work, found in the scope and content section of the database description of this thesis. /ourlegacy/node/19144 back

6. This book is available in special collections at the University of Saskatchewan Library, Saskatchewan Archives Board and Saskatoon Public Library Local History Room. back

7. Edgar Mapletoft et al. Fort Pitt History Unfolding, 1829-1985. (Frenchman Butte: Fort Pitt Historical Society, 1985) p. 101. back